Stop Using Kafka Everywhere

when message queues save your system and when they quietly make everything worse

Every engineering team reaches a moment where things start to creak. Requests spike unpredictably. Background jobs lag behind. One slow dependency begins dragging everything else down. That's usually the moment someone says: "Should we introduce Kafka?"

Sometimes that suggestion saves the system. Other times, it quietly makes everything worse. To know the difference, you need to understand the fundamental principle behind message queues.

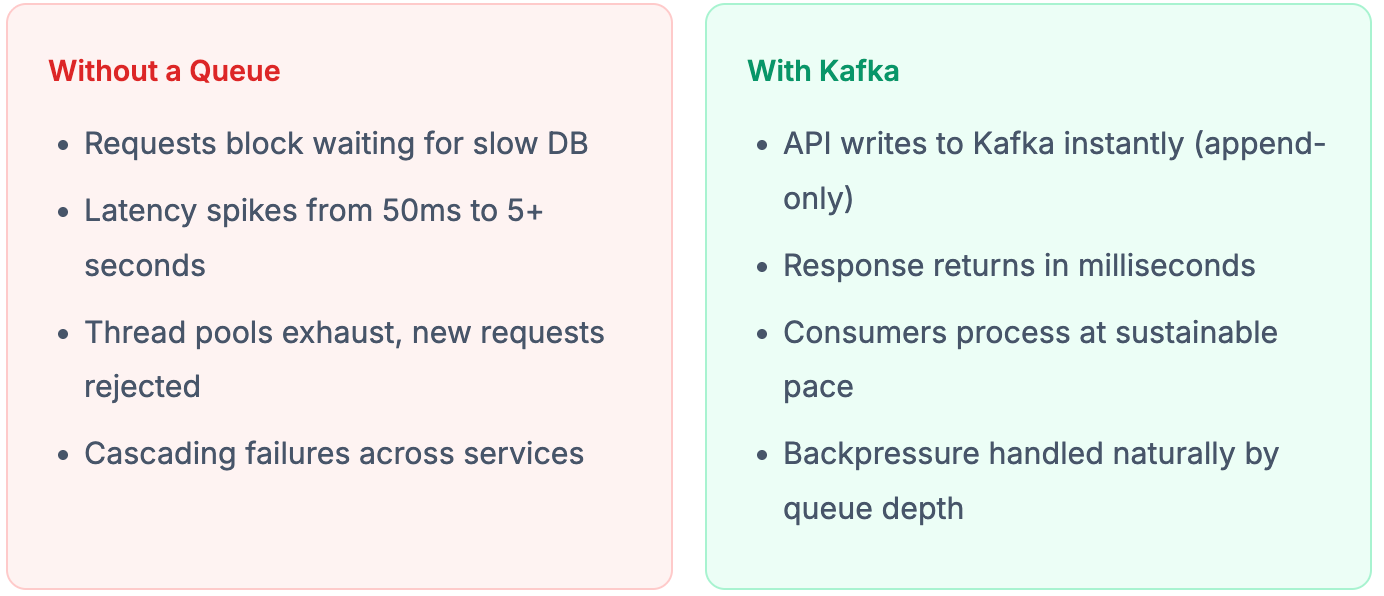

Before Kafka, before brokers and partitions, there is a simple truth: Different parts of a system run at different speeds. The moment you force them to move at the same pace, you create fragility.

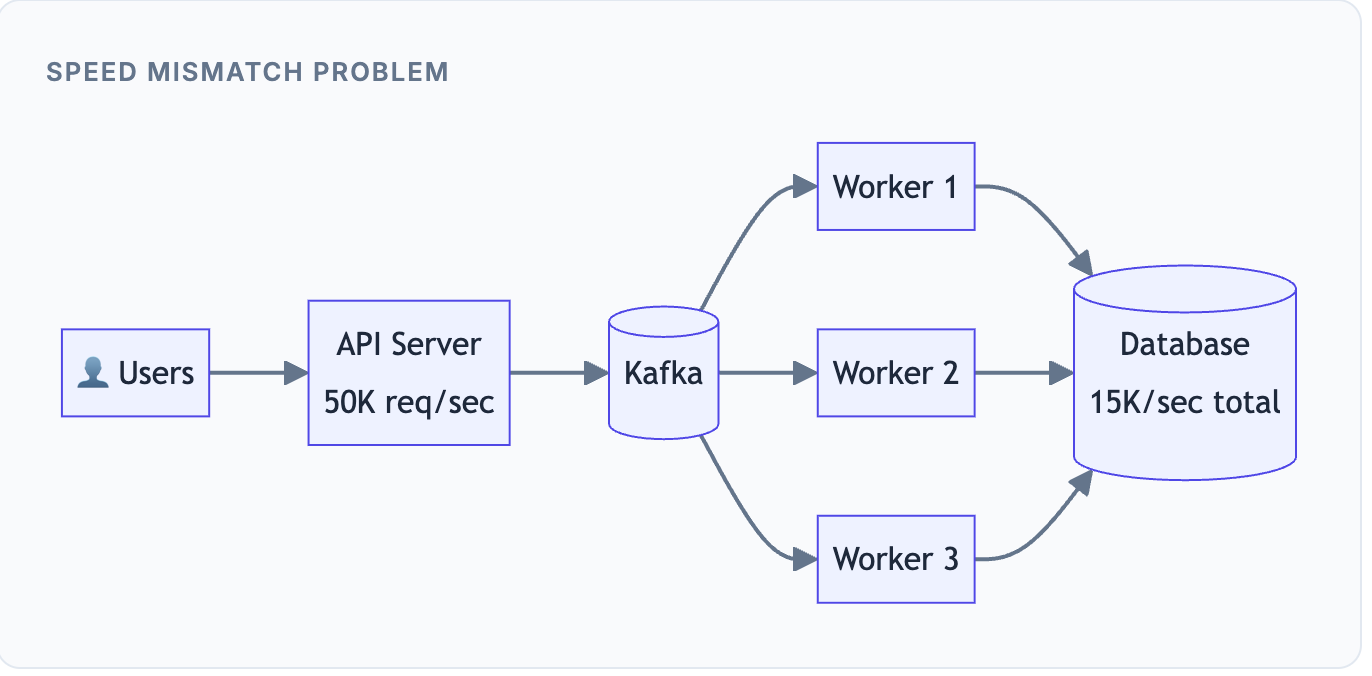

Think about it this way: Your API server can accept 50,000 requests per second because it's just receiving data. But your database can only write 5,000 records per second because it needs to persist data to disk, maintain indexes, and ensure consistency. When you directly connect the fast component to the slow component, the slow one becomes a bottleneck that drags everything down.

Queues exist to decouple time: Producers move fast, consumers move at their own pace, and the system survives bursts, failures, and change. Kafka is one powerful way to achieve this decoupling - but power only helps when you're solving the right problem.

When You SHOULD Use Kafka

1. When Producer Speed ≠ Consumer Speed

This is the most fundamental use case for any message queue, and it's where Kafka truly shines.

The Real-World Scenario: Imagine you’re running an e-commerce platform. Your API servers are designed to handle high concurrency - they accept HTTP requests, validate input, and return responses quickly. On a normal day, you might receive 50,000 requests per second during peak hours.

But here’s the problem: Your downstream systems aren’t that fast. Your database needs time to write records (disk I/O, index updates, replication). Your payment processor has rate limits. Your inventory service checks stock levels against a database. Each of these can only handle perhaps 5,000-10,000 operations per second.

Kafka uses an append-only log structure. Writing to Kafka is essentially just appending bytes to a file, which is incredibly fast. Your API can acknowledge 50,000 requests per second because it's not waiting for slow downstream processing. The consumers then read from Kafka at whatever pace they can sustain.

Any time one side of your system is faster than the other, a queue acts as a buffer that absorbs the difference.

2. When Traffic Spikes Are Unpredictable

Some systems experience steady, predictable traffic. Others face dramatic spikes that can appear without warning. Kafka excels at the latter.

The Flash Sale Scenario: Your e-commerce platform announces a flash sale at noon. At 11:59, you're handling 1,000 requests per second. At 12:00:01, it jumps to 100,000 requests per second as eager shoppers rush to grab deals. Three minutes later, it's back to 5,000 requests per second.

More Examples like Flash Sales, Marketing Campaigns, OTP Generation, Push Notifications, Log Ingestion etc

Why This Is Hard: If you provision infrastructure for peak load (100K/sec), you're wasting 99% of your resources during normal operation. But if you provision for normal load, you'll crash during the spike.

How Kafka Helps: During the spike, Kafka absorbs all 100,000 requests per second into its log. Yes, the queue depth grows temporarily. But your consumers keep processing at their steady 10K/sec rate. Within a few minutes after the spike ends, the queue drains back to normal.

Meanwhile, you can configure auto-scaling to add more consumers when queue depth increases, but this happens gradually over minutes - not the split-second response you’d need without a queue.

The Math: A 3-minute spike at 100K/sec produces 18 million messages. At 10K/sec consumption, it takes 30 minutes to clear. Your system survives because Kafka holds that buffer, not because you magically scaled 10x in milliseconds.

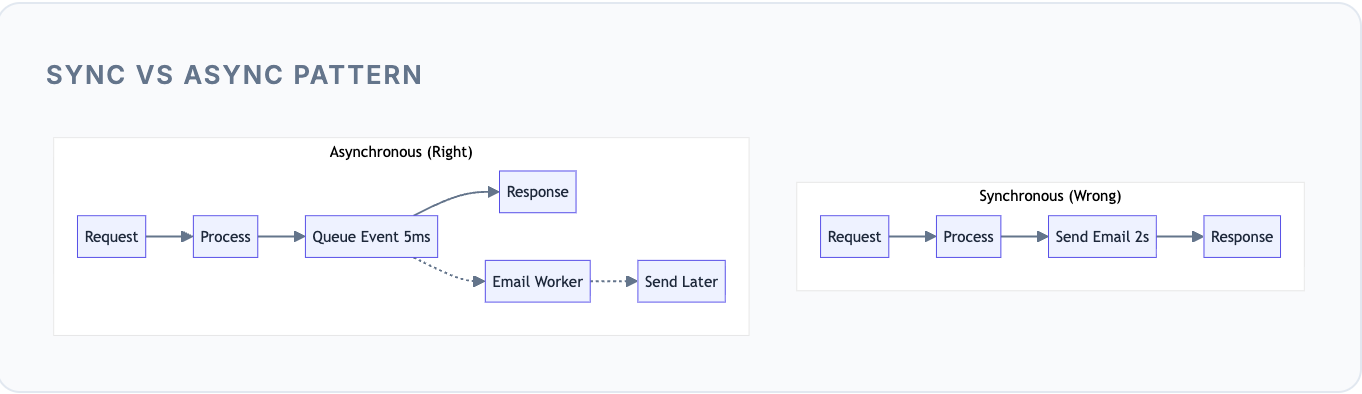

3. When Work Is Asynchronous by Nature

Some operations don't need to complete before responding to the user. Making users wait for these operations is both bad UX and wasteful system design.

The Email Scenario: A user signs up for your service. You need to send a welcome email. Should the user stare at a loading spinner while your server connects to the SMTP server, composes the email, and waits for delivery confirmation?

Similarly for Push Notifications, Image/Video Processing, PDF Generation, Analytics Events

Why Sync is Wrong Here: Sending an email might take 1-3 seconds (DNS lookup, SMTP handshake, server response). That’s 1-3 seconds the user waits unnecessarily. Worse, if the email server is slow or down, the user’s signup fails - even though email delivery isn’t critical to completing signup.

The Async Pattern: Your API pushes a “send welcome email” event to Kafka and immediately returns success to the user. A background worker picks up that event and handles the actual email sending. The user gets instant feedback, and the email arrives moments later.

If the user doesn't need the result immediately, don't make them wait. Push the work to a queue and respond instantly.

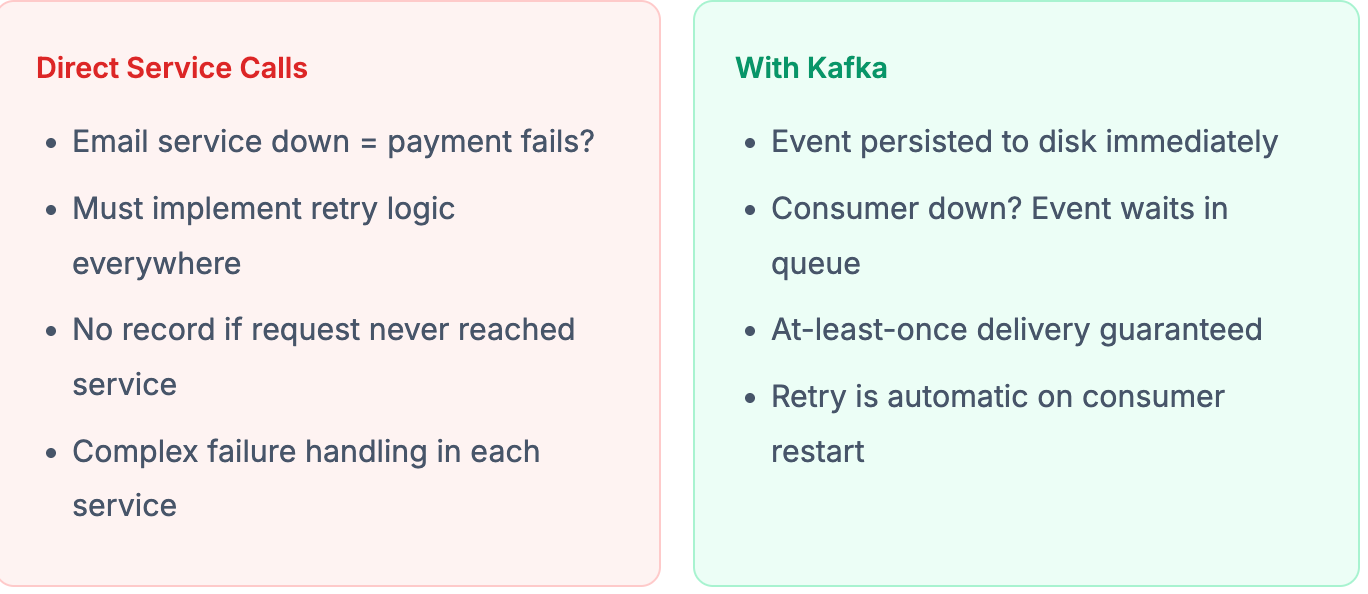

4. When Reliability Matters More Than Speed

Some events absolutely cannot be lost. A payment confirmation, an order placement, a financial transaction - these must be processed eventually, even if systems fail temporarily.

The Payment Scenario: A customer completes a payment. You need to: update their order status, send a confirmation email, notify the warehouse, update analytics, and trigger loyalty points. If any of these downstream services are down at that moment, what happens to the payment event?

More cases Order Confirmations, Financial Transactions, Audit Logs, Compliance Events

Kafka's Durability: When you produce a message to Kafka with proper acknowledgment settings, that message is written to disk and replicated across multiple brokers. Even if the consumer is down for hours, the message waits patiently. When the consumer comes back, it picks up right where it left off.

If losing an event is unacceptable, a durable queue like Kafka provides the safety net. The event is guaranteed to be processed eventually, even through failures.

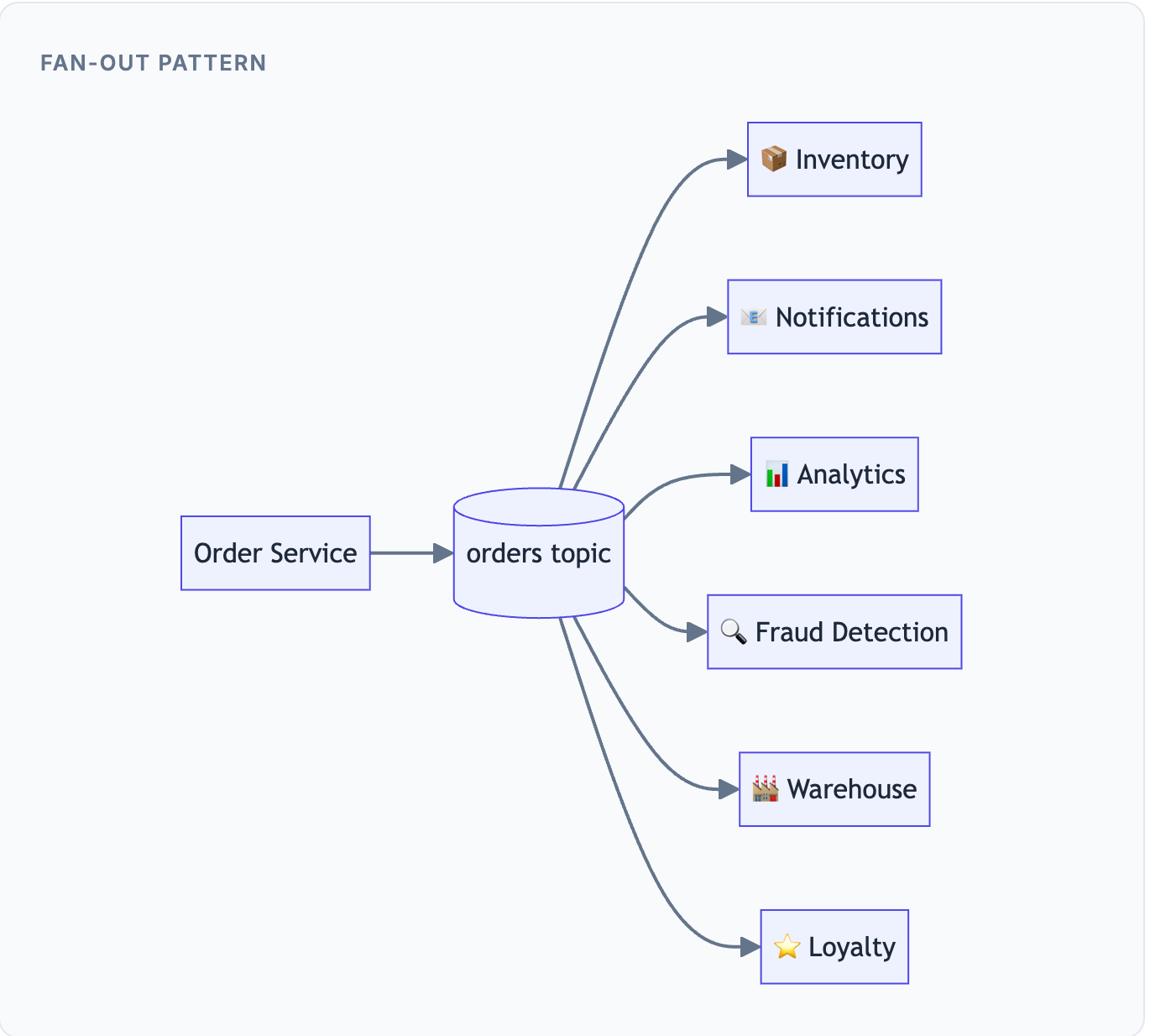

5. When Multiple Consumers Need the Same Event

This is where Kafka’s pub/sub model truly shines - the ability to broadcast one event to many independent consumers without the producer knowing or caring about them.

The Order Scenario: When a customer places an order, multiple systems need to react: Inventory needs to reserve stock, Notifications needs to send confirmation, Analytics needs to track the sale, Fraud Detection needs to evaluate risk, Warehouse needs to prepare shipping, and Loyalty needs to add points.

Without Kafka: The Order Service would need to know about every downstream service. Adding Loyalty Points? Change Order Service code. Adding Fraud Detection? Change Order Service code again. Each addition increases coupling and deployment risk.

With Kafka: Order Service publishes one event to the “orders” topic and walks away. Each downstream service subscribes to that topic independently. Adding a new consumer? Zero changes to Order Service. Each team owns their own consumer.

One event, many independent consumers, zero producer changes. Teams can evolve independently, deploy independently, and scale independently.

Other Scenarios Where Kafka Fits

When consumers evolve independently: Different teams work on different consumers with different release cycles.

When ordering matters: Kafka guarantees order within a partition - critical for state machines and sequential processing.

When retry logic would be ugly: Instead of implementing retry everywhere, let Kafka handle redelivery.

When you need horizontal scaling: Add more consumers to a consumer group to handle more load.

When you want replay capability: Kafka retains messages, letting you reprocess historical events for debugging or recomputation.

If direct service-to-service calls feel fragile, slow, or scary - you likely need a queue.

Related (Before reading further)

If you enjoy digging into how things actually work, I’ve been working on something larger.

I wrote an ebook that walks through 35 real engineering problems and system designs, focusing on how decisions break down at scale, what trade-offs actually matter, and the kinds of follow-up questions engineers run into in interviews and real systems.

It’s less about memorizing solutions, and more about learning the principles behind solving problems at scale - so you can reason through new situations, not just familiar ones.

When You Should NOT Use Kafka

This is the part people skip and later regret. Kafka adds complexity. Using it when you don't need it creates operational burden without corresponding benefit.

1. When You Need Immediate Request-Response

Kafka is fundamentally asynchronous. It’s built for “fire and forget” patterns, not for “call and wait for response” patterns.

The Login Scenario: A user enters their username and password and clicks "Login". They need an immediate answer: Are credentials valid? What's their session token? This must happen in milliseconds.

Similarly User Profile Fetch, Balance Check, Search Queries, Real-time Validation

Why Kafka Fails Here: To use Kafka for request-response, you’d need to: publish a request to Topic A, have a consumer process it, publish a response to Topic B, and have the original requester consume from Topic B. This adds 100-500ms of latency, requires correlation IDs to match responses, and creates complex error handling.

Use Instead: Direct HTTP/gRPC calls or database reads. If the user is staring at the screen waiting, Kafka is the wrong tool.

2. When Traffic Is Low and Predictable

Kafka’s power comes from handling scale and unpredictability. At low, steady traffic, it’s just overhead.

The Small App Scenario: Your internal tool handles 50-200 requests per second. Traffic is steady during business hours and drops to zero at night. You have a few background jobs that run every few minutes.

Internal Tools, Admin Dashboards, Small B2B Apps, MVPs etc

The Kafka Tax: Running Kafka means: managing a broker cluster (minimum 3 for production), configuring partitions and replication, monitoring consumer lag, handling broker failures, managing disk space and retention, and training your team on Kafka operations.

For 50 requests per second, this operational burden far exceeds any benefit. A simple database table with a worker polling every few seconds would handle your needs with zero additional infrastructure.

Use Instead: Cron jobs, simple database-backed job queues, or lightweight queues like Redis. Save Kafka for when you actually have scale problems.

3. When You Only Have One Producer and One Consumer

Kafka’s real value emerges with decoupling and fan-out. With a single producer and single consumer, you’re adding complexity without gaining the benefits.

The Middleman Problem: Service A needs to send data to Service B. You add Kafka between them. Now you have: two services to debug instead of direct call tracing, additional failure mode (what if Kafka is down?), consumer lag to monitor, and no real benefit since there’s no fan-out or speed mismatch.

Use Instead: Direct async HTTP calls, or lightweight queues like SQS or RabbitMQ if you need retry/durability. Kafka's power is wasted in 1:1 scenarios.

4. When Durability and Replay Don’t Matter

Kafka persists everything to disk. That’s its strength - but also overhead when you don’t need it.

Ephemeral Events: You’re broadcasting cache invalidation signals. You’re sending “best effort” metrics that are fine to lose occasionally. You’re coordinating temporary state between services. In all these cases, if an event is lost, it’s not a disaster — the next event will correct things.

The Overhead: Kafka writes every message to disk, replicates it across brokers, and retains it based on your configuration. For fire-and-forget events, this is wasted I/O and storage.

Use Instead: In-memory queues, Redis pub/sub or streams, or simple fire-and-forget HTTP calls. Match your tool to your durability requirements.

5. When Tasks Are Simple and Ordering Doesn’t Matter

Kafka guarantees ordering within partitions, but this guarantee comes with complexity. If you don’t need ordering, simpler tools work better.

Independent Tasks: You need to resize 10,000 uploaded images. Each image is independent - the order doesn’t matter. You need to send 50,000 emails - each is independent. For these “embarrassingly parallel” workloads, Kafka’s partitioning model adds unnecessary complexity.

Use Instead: Purpose-built task queues like SQS, Sidekiq, Celery, or BullMQ. These are simpler to operate and designed specifically for independent job processing.

More Warning Signs

Team can’t operate Kafka: Kafka requires operational expertise. Without it, you’ll face outages.

“FAANG uses it” reasoning: Cargo-culting doesn’t solve problems. FAANG operates at scales you probably don’t.

Large message payloads: Kafka is optimized for events (KB), not blobs (MB). Use object storage for large files.

Ultra-low latency requirements: If you need sub-millisecond latency, Kafka’s inherent latency (10-100ms) may be too high.

Kafka solves scaling pain, not design confusion. If your system is already messy, Kafka will just make the mess distributed.

Superb breakdown of the "when" vs "when not" decision tree that everyone skips. The 1:1 producer-consumer trap is especially common, I've seen entire teams add Kafka to what was basically a function call with extra steps. The flash sale math is dead-on too, most don't realize they're just moving a queue from one place(memory) to another(Kafka) unless there's genuine speed asymetry. Learned this one the hard way after debugging consumer lag that turned out to be solving a problem we didn't have.